‘Permission to Speak’, Solo Exhibition, Freud Museum, Maresfield Gardens, London, (2002).

Prior to this exhibition, I exhibited in 1999 in a Beguinage in Belgium. Beguinages were women only religious spaces founded in the 13th century. They are walled spaces where the gate is locked at night. On my first visit I was given a key and found a lone, trapped swallow flying silently and endlessly round and round inside the exhibition space. I opened the windows, freeing the swallow to fly across borders and boundaries WITHOUT a sense of the politics of space.

In Permission to Speak, a solo exhibition in Freud’s former home, the swallow was again a motif. The images of many swallows were drawn directly onto the white surface of blank jigsaw puzzles and placed on the walls of Freud’s former home. I then removed the drawings leaving an absence. In the upper rooms I displayed the absented birds on the walls of the space as though in flight, evoking the delight of rediscovering what was thought to be lost. In British folklore it is thought to be bad luck to have a live bird, or even a representation, in the home. This silent flock of drawn swallows was estranged from the blank frame of the jigsaw, leaving only absences in the enclosed space of the museum.

The title of the work ‘Permission to Speak’ refers to my childhood - a time when children were to be seen and not heard and required to speak only when spoken to.

In the library outside Freud’s study I placed a copy of my blank book lost for words….The book itself does not contain any printed information or instruction. A blank text that needs no translation. Would this blankness be ‘read’ the same in different languages? The cover of the book is white blotting paper a material for absorbing ‘knowledge’ perhaps. Only on this detachable surface is printed the title, ISBN and a quote from Maurice Blanchot: ‘About this book I had promised myself to say nothing …’ The book is also installed in other libraries in England, Europe, Japan, America and Canada as an act of intervention, a donation or a ‘gift’. Most of the libraries have no knowledge that the book is there, its placement evidenced only by a photograph.

“For this exhibition Anne Lydiat brings the images of many swallows drawn directly onto the white surface of blank jigsaw puzzles into Freud’s former home. In much British folklore having live birds or even their representation within the home is considered to bring ill luck. Elsewhere in Europe however, it is the custom that swallows entering the house are caught and smeared with oil so that their subsequent release will remove bad luck afflicting the house and its occupants. Maybe the hoped for outcome of such a ritual is really not so different to the release we desire from analysis.

The title of the work evokes a time when children were to be seen and not heard and required to speak only when spoken to. It also suggests the space opened up by the so-called ‘talking cure’ of psychoanalysis where one might finally articulate the things that had so long gone unsaid. Yet it is curious that this work itself remains determinedly soundless. Consider though that it is now October and the swallows are long gone and the skies are full of their absence. That these images are on jigsaw puzzles is surely significant. Jigsaws demand completion: the point is to make all the pieces fit. Whether in jigsaws, art or analysis we seem to want things to come together wholly and meaningfully with no awkward missing pieces. Such completeness is denied here. The jigsaw pieces forming the birds have been removed, separated from their blank grounds. It is questionable whether they are set free or lost. Anne Lydiat has long specialised in this territory of uncertainty and ambiguity. The work refuses conclusion, rather it lodges a poetic splinter in the imagination that is difficult to remove.”

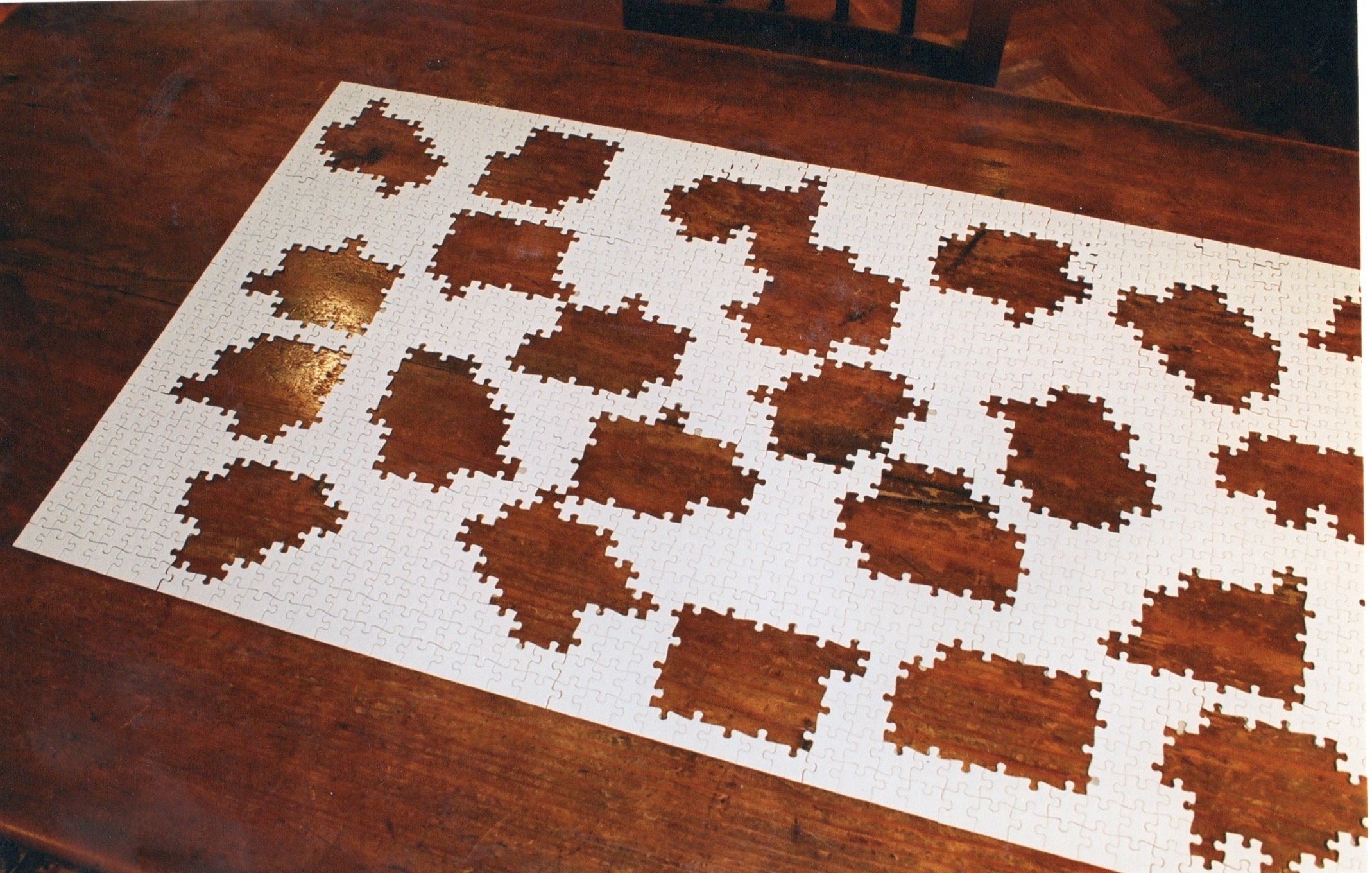

“Permission to Speak, recently at the Freud Museum, explored the ability of the blank form to assimilate loss, silence and nothingness. The artist placed a number of blank, white puzzles on tables in the house. Each one was made with proportions similar to the surface on which it sat. Some, accordingly, were stout and square while others took off like an epic frieze or tapestry. Chairs were left drawn up to the tables as though puzzlers had wandered off for a break and could return soon to resume their strange and meticulous work. The puzzles were incomplete with oddly shaped patches of absent pieces. The shape of the holes revealed the surface of the tables underneath and suggested that there may be some hidden scheme linking the missing elements. It was only on going upstairs that this scheme was revealed. The pieces that had been separated from the blank puzzles were found to contain images of swallows, drawn in outline and then penned in to create dark silhouettes. Exhibited on the walls of the emptiest room in the house these pieces were joined together, their sudden dark forms suggesting startled flight, a rising flock. They appeared caught in the reluctant act of assuming representation.”