Meaning Making, Making Meaning

Embedded within the ordinary things we say, within the cliches of our everyday speech, are knots of assumed meanings. To say of someone that they are housebound imports a set of assumptions about the value, or otherwise, of one set of activities as against another. These knots, their implicit associated valuations of one thing over another and questions about their truthfulness, provide one stream of meaning within the body of work that Anne Lydiat has been doing. One can group together, for example, ‘Housebound’, ‘Going Dutch’, ‘Thin End of the Wedge’, ‘Heart of Stone’ and remark that by illustrating the cliché she asks us to consider what is being siad. A displacement or substitution takes place, which gives pause.

Displacement, or perhaps upsetting the apple cart, is also a component in those paintings whee an apron is either cut from the canvas surface or attached to it. The concatenations of the brand name of the apron—‘Superior’—with the kind of apron it is (a craft apron), and the reverberations of being tied to one’s apron string, lead to a rich tangle of meanings. Something very similar occurs in the ‘White Work’ paintings and, very eloquently, in the group of three titled respectively ‘The Craft of Art, ‘The Art of Craft’ and ‘Inside, Outside’. In this latter group, the embroidery hoop attached to the quilted surface takes on added connotations of both head and mirror.

Issues of appropriateness of means to context—the rules of the game if you like—are equally a part of those works. Why certain procedures produce one class of objects and another set a lesser class is a mystery. ‘Falling Between Two Schools’ ironically portrays Anne’s sense of isolation from an institutionalised version of the practices of fine art. She pays a great deal of attention to the ways in which she makes things. Indeed, the sense of what she makes as having meaning, derives in part from its connection to a set of common practices. That commonality is identified in her personal history, (as for example in ‘Ironing Out the Wrinkles’ and ‘Three Had Reel’), and more generally, in the community of fellow practitioners. The former being a sub-set of the latter, the inference is that more than ways of doing are shared.

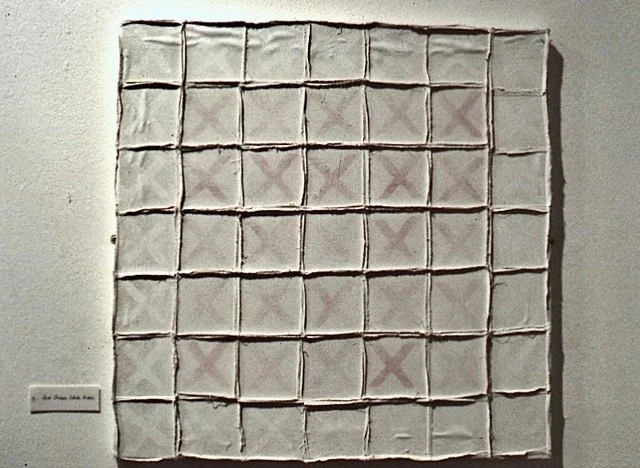

The use of the cross stitch as a means of putting things together is both celebrator of the (X marks the spot) and confrontational (crossing out, the exclusion of domains of material practice from high art significations). At the same time these works, in particular the quilts, ‘White Work’ and ‘By the Yard’ draw on a cultural armature which has something in common with the work of Robert Ryman, Agnes Martin and Sol Le Witt. That is to say, the means of production of their surfaces, simple juxtaposition and repetitive addition, leads to variations in quality, divergences from the norm. One can think of this as the margin of error. However, there seems to be a big gap between that as a rationalisation and the experience of ineffability that is the product of looking at the things. In ‘Purity and Danger’, Mary Douglas identifies dirt as ‘matter out of place’ and therefore, since it is free of categorial constraint, potentially highly volatile as a source of meaning. The signification that error has in the context of the kind of making that Anne is using, seems somewhat similar. Enlarging the frame slightly one might also say that Anne’s procedures for making are an error in the domain of fine art practice. This is a source of strength.

Richard Deacon, April 1987

‘Waiting for the Seventh Wave’. pp.7-8

Published by Ikon Gallery, Birmingham.

Edition of 500 May 1987.

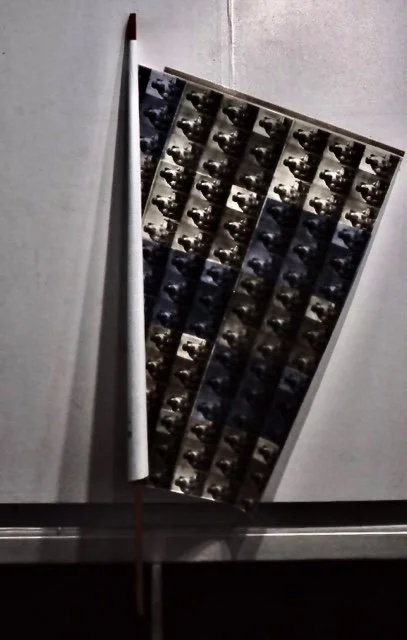

‘By the Yard’, Anne Lydiat 1987, which uses Diego Velázquez’s The Needlewoman from about 1640-49: it shows one woman engaged in the act of sewing. As she is looking down at her work, its role as a portrait is limited. Much of what it has to say is about what she is doing with her hands, her skill, and peaceful concentration.

‘White crosses and red kisses’, Anne Lydiat 1987