‘I wonder where you are?’

(Wonder: an emotion comparable to surprise that people feel when perceiving something rare or unexpected.)

A few years ago I made a decision to make some changes to my sense of being. It seemingly takes something that threatens our way of being to make us contemplate change, and I was at that point. I needed time and space in order to reflect, to reconnect with my artistic practice and my sense of self - to attempt to lose myself as a creative condition.

Free at last to embark on my expedition into the territory of self, that started with the desire to ‘get lost as a positive action’, I wondered what would I do with this aporia, this space of absence and dis/location. What if I lost myself and like Hansel and Gretel couldn’t find my way home.

In ‘Lost and Found. The Location of Disorientation’, Irit Rogoff writes:

“One of the surprises of exploring the discursive and linguistic articulations of the states of being lost, is that they are always aligned with a form of location either concretely topographical or as a state of mind – ‘lost in time’, ‘lost in space’, ‘lost in the woods’, ‘lost in thought’, ‘lost horizon’, ‘she has definitely lost it’ – in every known metaphorical configuration ‘being lost’ is the active state of existing between paradigms, no longer in one nor yet within the other. Thus being lost is never unlocatable but always a some-where and a some-thing of ‘inbetweeness’. It is this duality, this ambivalence between nowhere and somewhere that gives the state of ‘being lost’ its frisson of excitement, for we quickly understand that within it we can trace links to great moments of ‘becoming’, of transition and of perception.”

The difficulty I experienced was that as soon as I began to wonder how I might get lost, the possibility of achieving this desired state of being seemed more remote than ever. How does one deliberately get lost? Where and how might I attain the “great moments of ‘becoming”, of transition and of perception’ that Rogoff posits as a possibility and how might my deliberately attempting to be lost as a space of creativity bring this about?

The first stage of my expedition was to travel alone to Europe. I planned to visit the beguinages (bejinhof), women only spaces and some of them silent spaces, mainly in Belgium. Traveling alone, and in silence, I wondered whether silences would be the same in different countries eg. a French silence, a Russian silence or a Japanese silence and how might these silences be translated? I made a blank book, an authored space of silence needing no translation, entitled lost for words… Where might this book be placed? What would be its space – a space of ‘absence’ perhaps, or an interstice?

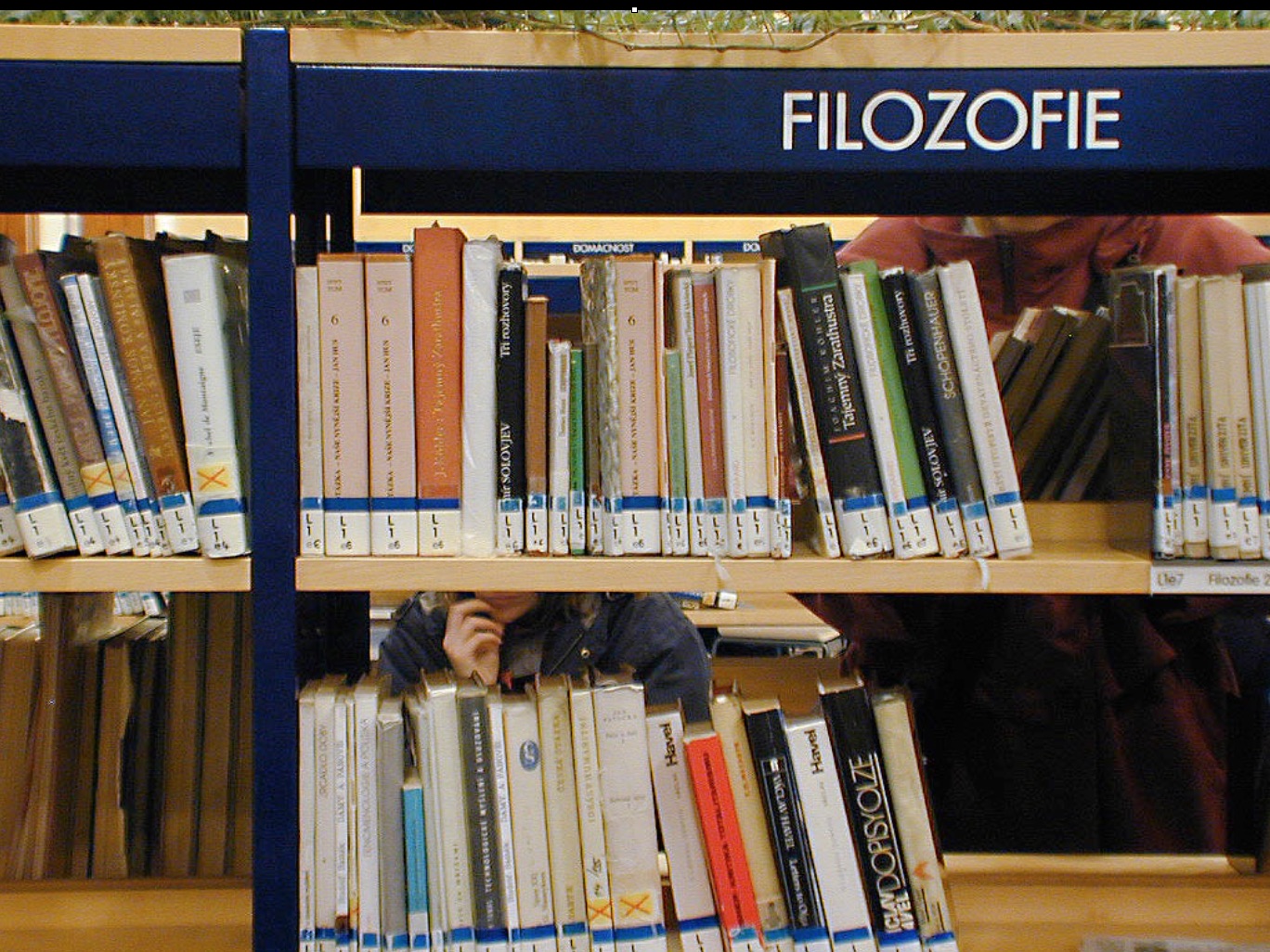

…I subsequently secretly put the book in libraries wherever I travelled, as an intervention, a donation, or a gift. I placed ‘lost for words…’ in the Philosophy Sections, under ‘L’ Lydiat, usually in between Kant and Lyotard! I then took a photograph of the book in its contingent space and left it as an officially unacknowledged presence, ‘a some-where and a some-thing of ‘inbetweeness’. What was I trying to say in this interstitial space of absence – was I trying to speak of my own creative state of being lost? I wondered would it, or I, ever be found?

In a text that accompanied my exhibition Permission to Speak, Freud Museum 2002, Dr Nicky Coutts wrote:

“Lydiat has been exploring ideas surrounding personal loss and displacement for several years. Her work hankers and probes at the furthest outreaches of the graspable in its quest to unravel and represent conditions of absence, silence and loss. What does it mean to be lost? Is it possible to be lost to ourselves? Can an individual experience their own absence? Can we knowingly become lost? Lydiat explores these questions through the ambiguities of language and their reflection in form. A recent piece, elegantly cementing the two together is ‘lost for words…’ now permanently installed at the Freud Museum. ‘lost for words…’ takes the form of a book with a white blotting paper cover, its title printed lightly on the front and on the spine. The pages within it are blank. ‘lost’ has been translated by Lydiat into an infinite repetition of absence, words are unspoken into silence, promising to say nothing. It is only the marks made by those who handle the book that reassert its presence, confirming it found. The work only exists at the threshold of its own disappearance, at the moment of its transformation into a secondary phase.”

As Rogoff states “being lost is never unlocatable” and the photograph became the means of locating my book, and me, in time and space. Why did I need to take a photograph? Was taking a photograph to satisfy the desire to capture the moment for myself, as proof of my existence? Would the unrecorded experience of the moment not have been enough? I wondered what would have been lost?

As a means of getting lost in the city I utilised the Situationist’s derive. (A derive is ‘an unplanned tour through an urban landscape directed entirely by the feelings evoked in the individual by their surroundings, served as the primary means for mapping and investigating the psychogeography of an area…with the ultimate goal of encountering an entirely new and authentic experience – Wikipedia.) This time I decided not to take a photograph to locate myself as I negotiated the city – the artistic flaneuse, Instead, I made drawings of the traces of my routine movements whilst walking.

In ‘Wanderlust: A History of Walking’, Rebecca Solnit writes:

“Walkers are 'practitioners of the city,' for the city is made to be walked. A city is a language, a repository of possibilities, and walking is the act of speaking that language, of selecting from those possib”lities. Just as language limits what can be said, architecture limits where one can walk, but the walker invents other ways to go.”

The chance, or serendipity, of my drawings was determined by the duration of time and space and the seismic movement specific to each journey creating maps to get lost by perhaps.

IMAGE OF TRAVEL DRAWINGS

In a Field Guide to Getting Lost, Solnit writes:

“Without noticing you have traversed a great distance; the strange has become familiar and the familiar if not strange at least awkward or uncomfortable, an outgrown garment. And some people travel far more than others. There are those who receive a birthright an adequate or at least unquestioned sense of self and those who set out to reinvent themselves, for survival or for satisfaction, and travel far…”

I felt I had ‘traversed a great distance’ both geographically and emotionally on my personal expedition. I had been there, and safely returned back…

This is a place of waiting – waiting for the tide, waiting for the fishing boats to come back with their catch and waiting for news of you on your artistic expedition to the Arctic. I look out to sea from this place and I wonder where you are? My phone rings – I hear your familiar voice from your faraway place over the sea. I tried to imagine where you are and I wait for you to safely return back…

The Dutch born artist Bas Jan Ader, left his wife and his California home on 9 July, 1975 on a expedition as a work of art. He set sail alone in his small boat Ocean Wave, across the Atlantic Ocean to his motherland as part of a three part performance art piece “In Search of the Miraculous’: One Night in Los Angeles (part one) an estimated 60 days at sea (part two) and One Night in Amsterdam (part three) - he never arrived presumed lost at sea. His boat was eventually found in the following April (1976) by a spanish fishing trawler approximately 150 miles off the coast of Ireland. Ocean Wave was subsequently stolen and Ader’s wife never saw it, or her husband again.

What was the miraculous that Ader was searching for? Perhaps he too was venturing on a personal expedition trying to attain the “great moments of ‘becoming”, of transition and of perception’ that Rogoff posits as a possibility. I wondered if he was trying to get lost as a positive action. Or was it “the agonising, isolated duration spent adrift on the ocean that allows the mariner a unification with nature and self?” that Coleridge explores in the Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Was this the desired state of being that Ader was searching for in his attempt to return to his ‘motherland’?

“…Like the great adventurers Colombus or Magallanes, the artist’s curiosity for what is beyond the ocean and the borders of civilisation is expressed by the balance between the physical and the spiritual in his work, which, void of any human influence, has a sublime and mystic tone, making his artwork unique…”

In the DVD ‘Here is always somewhere else’ Rene Daalder, was commissioned to explore the myth of his lost friend. We are presented with the image of Ader’s wife Mary Sue where she personifies the archetypal image of the woman ‘waiting’ (like Penelope) for her traveling man to return whilst symbolically being at home.

‘Penelope and her Suitors’, J W Waterhouse

Excerpt from a telephone conversation with Mary Sue-Ader Anderson. Los Angeles. 28 May 1976. ‘AVALANCHE’, Summer 1976

MSA: I was waiting there for him. I was positive he would show up there at that time, and then when he didn’t, I was convinced he would show up any time from then on through December.

LB: How long did you stay in Holland?

MSA: I stayed until one week into September…

LB: When he didn’t arrive what happened?

MSA: I wasn’t discouraged by the time I left, I expected him any week. When he didn’t arrive within his set time period we decided that he had grossly miscalculated the time it would take him on such a small boat, and a lot of experienced sailors said that he could make it but it would probably take him up to 150 days. Se we waited…

That was in 1976 and there in the video, some thirty years later after her husband disappeared, surrounded by his art works, memorabilia (and a rat in a drawer) she is still waiting. An artist herself (you see her paintings in the background) she appears to have lost all sense of herself. It seems she has invested her whole being into keeping Ader’s memory alive.

I wonder why she is still waiting? I began to question Mary Sue Ader-Anderson’s passive acceptance of her lot, as the wife waiting at home for her artistic hero to return.

In ‘are we there yet’, Emma Cocker writes:

“Beckett draws attention to the contradictory nature of waiting and to the sense of expectation therein; for it is a space of simultaneous hope and doubt, of both desire and disenchantment...The duration of waiting is equally ambiguous, for it is inevitably too long and yet somehow never enough. Think of those involuntary moments of indecision when the unfulfilled wait is finally abandoned.

The nature of unresolved waiting, when an end or destination remains at a distance, creates the liminal experience of being not-yet-there; a period of restlessness or temporal vacuum…”

"Waiting on the Shore" On 10 August 2002 a sculpture entitled "Waiting on Shore" was officially unveiled by Capt. Frank Devaney and Mrs. Myra Bruen-Curley.

She writes that Bas Jan Ader believed that setting sail alone in a small boat, surrendering himself up to the forces of the sea, was the highest form of pilgrimage.

In his search for the miraculous was Ader lured by the call of the sea, as the conquering artistic hero or did he perhaps identify with the melancholic tragedy of ‘The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst’ (Dean implies that Ader knew of Crowhurst’s tragic voyage before he set sail). I wondered if he intentionally got lost?

In Teignmouth Electron, Dean, again presents a ‘romanticised’ version of the disappearance at sea of Donald Crowhurst in 1969. He was one of nine competitors who set out in the first single-handed non-stop around the world yacht race. He set sail from Teignmouth in his boat Teignmouth Electron that ended with his the loss of his sanity and his life to the sea.

Even as recently as the 20th century it would seem that waiting at home was the order of the day for many women, particularly those whose husbands and sons were at sea, or at war. There are very few signs to be found of the lives, especially the bravery, and achievements of these women. My searches found that there are various monuments to the bravery of those who leave the safety of the shore (usually those male heroes who ‘failed’ to return) and none that celebrate those who were left behind. I found one memorial that commemorates both the men from the Rosses Point parish and the Sligo community who lost their lives at sea, and their women who waited.

In 1996, Tacita Dean began a series of artworks collective entitled Disappearance at Sea, inspired by remarkable stories of male personal encounters with the sea. In the video ‘Here is Always Somewhere Else’ about the disappearance of Bas Jan Ader, she talks of the type of person (these lone sailors) who under take these voyages are. Hers is a romantic notion of the male hero – she talks “of a test of their bravura…of their very soul”.

Crowhusrt aboard Teignmouth Electron

“His (Crowhurst’s) story is about human failing, about pitching his sanity against the sea, where there is no human presence or support system on which to hang a tortured psychological state. His was a world of acute solitude, filled with the ramblings of a troubled mind… ”

There have been many films, books and articles written about Crowhurst’s story and very little about Clare, the wife he left behind, who was known in the press as the ‘sea widow’. Was it because of their children that she did not seek the spotlight or make the headlines? I wondered where she was?

Recently I attended various lectures on expeditions both scientific and artistic, where I was struck by the absence of references to women except for the fact that their husbands, fiancés had named islands and glaciers after them!

“One of the greatest powers that mapmakers have is their power to name.” Feminist language specialist Dale Spender thinks that the division of power in naming is so fundamental and universal that she describes the world as composed of “The Namers” and “The Named”.

It would seem that the restless desire for exploration has predominantly been the male preserve i.e. Arctic/Antarctic exploration has spawned a long history of success and failure. The prodigal sons who never returned? Why do we know so much about these men?

I asked, are there any women explorers? It would seem not! I wondered where they were?

“In the backdrop of nearly every polar explorer’s story is the classic tale of Penelope, the devoted wife in The Odyssey who waited a decade for her husband to return from war. Like Homer’s Odysseus, the likes of Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton and Fridtjof Nansen spent years away from home. But unlike Penelope, their wives did more than weave tapestries and ward off unwelcome suitors. Women such as Lady Jane Franklin, whose famous letter-writing campaign succeeded in dispatching 13 ships to the Arctic in 1850 in search of her husband’s lost expedition, or Jo Peary, who, in 1891-92, was the first woman to accompany an expedition to the Far North…

In conquering unknown territory, polar wives were as daring as the explorers they married. While they may not have made headlines or found immortality in the history books, the wives of polar explorers overcame adversity and broke barriers surrounding the accepted social spheres of their time.”

Below is my homage to some of the amazing women explorers and travelers that undertook these varied and seemingly unacknowledged expeditions of their own:

Liv Ragnheim Arnesen (born 1 June, 1953) Arnesen led the first unsupported women’s crossing of the Greenland Ice Cap in 1992. In 1994, she made international headlines becoming the first woman in the world to ski solo and unsupported to the South Pole – a 50-day expedition of 745 miles (1,200 km).

Gertrude Bell (1868-1926) - explored, mapped Greater Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Arabia.

Louise Arner Boyd (1887-1972) known as the "ice woman," she was an American who repeatedly explored and photographed the Arctic Ocean; she was also the first woman to fly over the North Pole.

Sophia Danenberg (1972-) - first black woman to reach the summit of Everest.

Laura Dekker (1995-) - youngest person to sail around world solo.

Moira Dunbar Originally from Edinburgh, Dunbar emigrated to Canada in 1947, where she studied ice movement for the Joint Intelligence Bureau of Canada. She later moved to the Defense Research Board in 1952, where she fought notions that a woman couldn’t go to the Arctic on reconnaissance planes of the Royal Canadian Air Force. She co-authored Arctic Canada From the Air with Keith R. Greenaway in 1956. She logged over 600 flight hours and became the first woman to sail as part of a science crew on board a Royal Canadian Navy icebreaker.

Amelia Earhart (1897-1939) - first woman to fly solo across Atlantic

Gertrude Ederle (1906-2003) - first woman to swim English Channel

Lady Hay Drummond-Hay (1895 - 1946) - first woman to go round world by air (in a Zeppelin)

Barbara Hillary (1931-) - was the first known African-American woman to reach the North Pole, which she did at the age of 75 in 2007. She subsequently reached the South Pole in January 2011 at the age of 79, becoming the first African-American woman to reach both poles.

Mae Jemison (1956-) - first black woman in space.

Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner (1970-) - first woman to climb all 14 eight-thousander mountains without supplementary oxygen.

Annie "Londonderry" Kopchovsky (1870–1947) - first woman to bicycle around world.

Annie Smith Peck (1850-1935) - first person to climb Mt Nevado Huascarán.

Sally Ride (1951-) - first American woman in space.

Edith "Jackie" Ronne (born October 13, 1919 - June 14, 2009) was an American explorer of Antarctica and the first woman in the world to be a working member of an Antarctic expedition. She is also the namesake of the Ronne Ice Shelf.

Namira Salim (Urdu: نمیرا سلیم; born 1975 in Karachi, Pakistan) an explorer who is the first Pakistani to have reached the North and South Poles. She may also become the first Pakistani to travel into space on the world's first commercial space liner Virgin Galactic. Salim has said she hopes her achievements are an inspiration for Pakistani women.

Hester Stanhope (1776-1839) - first modern archaeology in Holy Land; traveled unveiled, dressed as a man.

Valentina Tereshkova (1937-) - first woman in space.

Jessica Watson (1993-) - youngest person to sail non-stop, unassisted around world (but not meeting WSSRC criteria).

Could it be the very success of these women’s achievements that renders them invisible to us? If we acknowledge, or dare I say celebrate, their endeavours might that somehow devalue, or put into question those feats of heroism that have become the embodiment of the tragic male hero who failed to return, that we read so much about? These remarkable women did not make a decision to become intentionally lost, they were t/here all the time, just waiting to be found and to rightfully take their place in our histories.